2024

It's a shame that concrete doesn't burn

RAQUEL MEYERS

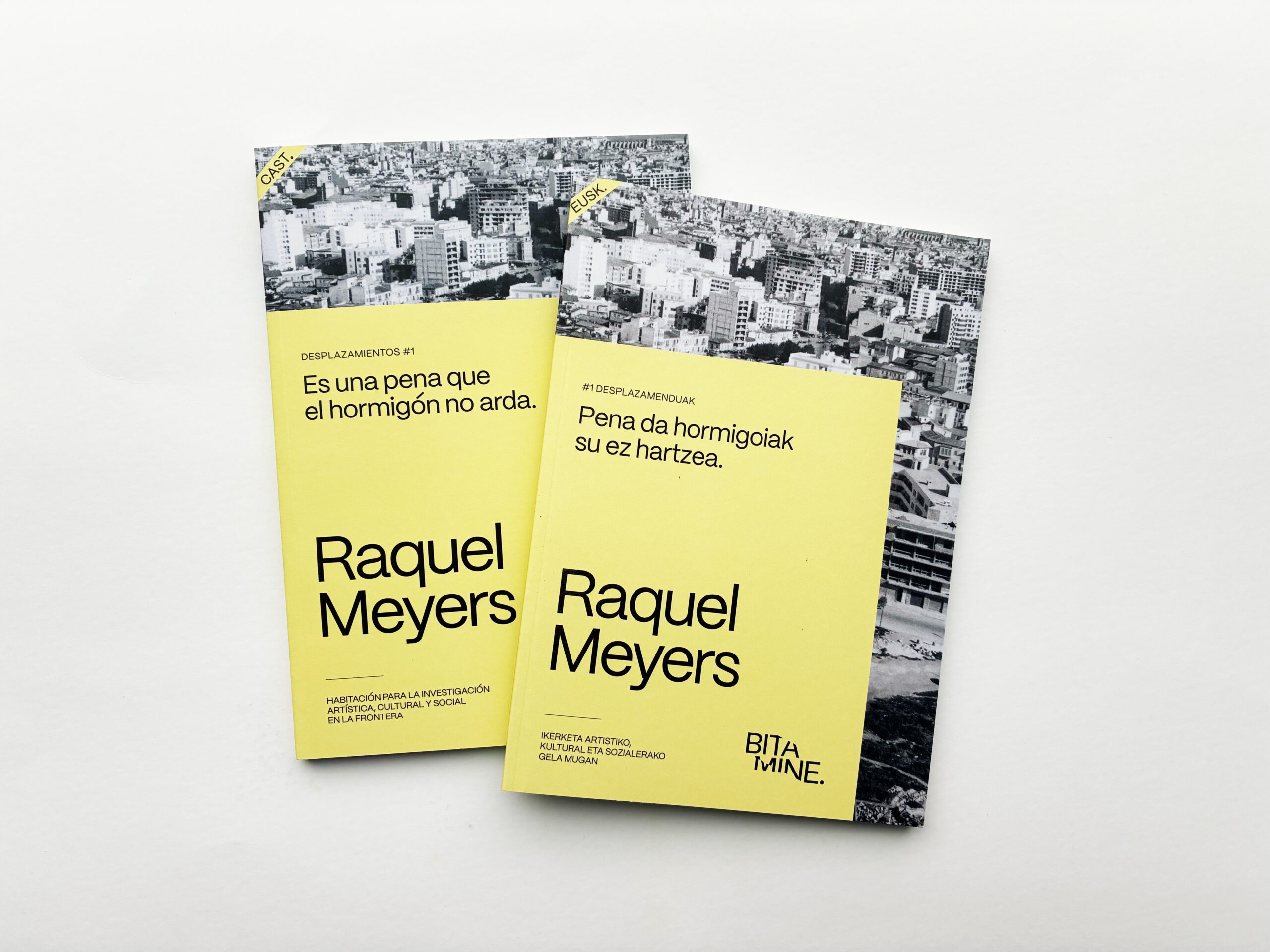

Bitamine Kultur Elkartea, a space for artistic, cultural, and social research at the border, located in Irun (Basque Country), in partnership with Fundación Casa Planas. Image and Tourism, based in Palma de Mallorca, launched in 2024 a fellowship programme aimed at researchers residing in the Basque Country.

The programme seeks to develop and produce projects that reflect on the sociocultural impact of tourism. The research is grounded in the activation of the Tourism Archive at Casa Planas (Planas Archive).

Through their strategy of outward projection and the creation of new connections across the national territory, both organisations began their collaboration in 2022 to foster research and contemporary creation. They share a mission to generate spaces for debate and critical thinking in order to rethink new ways of studying mobility and displacement, from a more responsible perspective rooted in respect and care, with a strong ecosocial and decolonial orientation.

In this context, they launched an open call for artistic research projects addressed to artists, researchers, curators, etc., who live and work in the Basque Country, with no restrictions regarding discipline or field of study.

DESPLAZAMENDUAK / DESPLAZAMIENTOS offers the possibility of activating the research at Casa Planas in Palma de Mallorca through a one-month residency, while the rest of the research is carried out in the Basque Country, with access to Bitamine’s space in the Bidasoa region.

The selected project was It’s a Shame That Concrete Doesn’t Burn by Raquel Meyers.

Alongside the development of her research, a programme of activities was organised in which the artist presented the outcomes of her investigation—collected in this publication—within the framework of the International COSTA Congress (Sustainable Tourism and Culture Observatory), organised by Casa Planas in Palma de Mallorca in October 2025, as well as a series of public presentations held in the Basque Country.

Drawing on an artistic research process carried out within the Desplazamenduak / Desplazamientos Fellowship #1, Raquel Meyers constructs a critical artefact in the form of an expanded essay that stirs the rubble of progress to reveal the other side of the modern miracle: concrete as a symbol of control, greedy tourism, exclusionary urbanism, and the architecture of forgetting. It’s a Shame That Concrete Doesn’t Burn is a provocation not aimed at the material itself, but at the model that has elevated it as the foundation of an uninhabitable world.

Raquel does not merely observe; she interrogates. With the cities of Palma and Irun as her stages, this project becomes an emotional and political archaeology of late capitalism: tourism, cement, expulsion, precarity, algorithms, and social strata. A collage of memory, archive, teletext, and an urbanism that does not welcome, but repels.

Meyers’ gaze is radical: there is no redemption in the postcard the artist sends us. Her critique filters through headlines from the 1970s and contemporary statements alike, revealing that the official narrative of development has always been an aesthetic operation of whitewashing. Because concrete does not burn, but it suffocates. Because modernity did not build homes, but markets. Because the city, as Harvey argues, is no longer a space for living but for accumulation. And because, as Fisher reminds us, capitalism has succeeded in making it impossible for us even to imagine something else.

This book offers neither solutions nor nostalgia. It is a cry from the margins, a form of militancy through images, an act of sabotage against the domestication of the public sphere and the commodification of the commons. An uncomfortable reminder that what we call progress was—and continues to be—a machine for producing inequality, disenchantment, and dispossession. That the public and the commons are our habitat, and we are losing them.

If anything burns here, it is not the concrete: it is the urgency to imagine another city, another landscape, another way of inhabiting.

Helga Massetani Piemonte

Raquel Meyers’ project is a compelling proposal for speaking about what does not move: concrete. This material is the great invention of the twentieth century, an element that has gradually eroded our landscapes and imaginaries over the last hundred years, becoming the backdrop of the tourist landscape to the point of becoming almost imperceptible.

Among the more than 5,000 postcards produced by Casa Planas, it is striking to observe how concrete appears as a protagonist in around 80% of them, presented as an image of modernity, progress, and even as an object of desire or admiration. Far removed from this reading, a more conscious awareness of the water consumption involved in these constructions and the eternal waste they leave on the planet confronts us with a reality that urgently demands a revision of our landscapes and imaginaries.

This artistic research helps us understand how we have internalised the desire for cementation to the point of normalising the idea of building “a wonderful bridge in the Mediterranean.” Raquel Meyers has extracted documentation that helps to trace the boom of late-Francoist Spain, using the cities of Irun—shaped by industry—and Palma—shaped by tourism—as case studies.

Alelí Mirelman – Casa Planas

Galería

PARTICIPANTS OF THE COMMUNITY